For the majority of my life, the stories of my childhood have been recounted through a veil of sarcasm and dark humor - a well-practiced, defense mechanism designed to make the unbearable palatable for an audience of strangers and friends alike. Laughter was a shield,, a carefully constructed barrier to insulate myself from confronting the truth of my own past. I used the sarcasm to mask the trauma from others, but most importantly from myself. My internal structure was built on a foundation of profound and unrelenting neglect, insidious psychological abuse, and a meticulously executed campaign of parental alienation - alienation that not only alienated my father from his children, but even I was alienated from my own past, my pain, and the truth of what was done to me by the one person a child is supposed to be able to trust, their mother. To be a better father, and man, for the sake of my own young children, I must now examine without the softening effect of sarcasm my past and my mother to truly understand the man I am - the father I strive to be and the survivor I have become. I must be willing to walk through the ruins of that history, to sift through the debris of what was done to a child - to me - to ensure my children don't ever endure torment that'll last a lifetime. This is the truth of what I endured. This is how I continue to survive. This is what I fight to protect my children from.

My earliest memories, or emotional phantoms to be more accurate, are of rejection. As early as I can recall - as I can feel - my mother, Patricia Kathleen Elizabeth Chapman, rejected me. I clearly recall feeling like a burden, unwanted, and unloved. This simple reality, one simple relationship between 2 people, forever and permanently impacted that child’s life - my life.

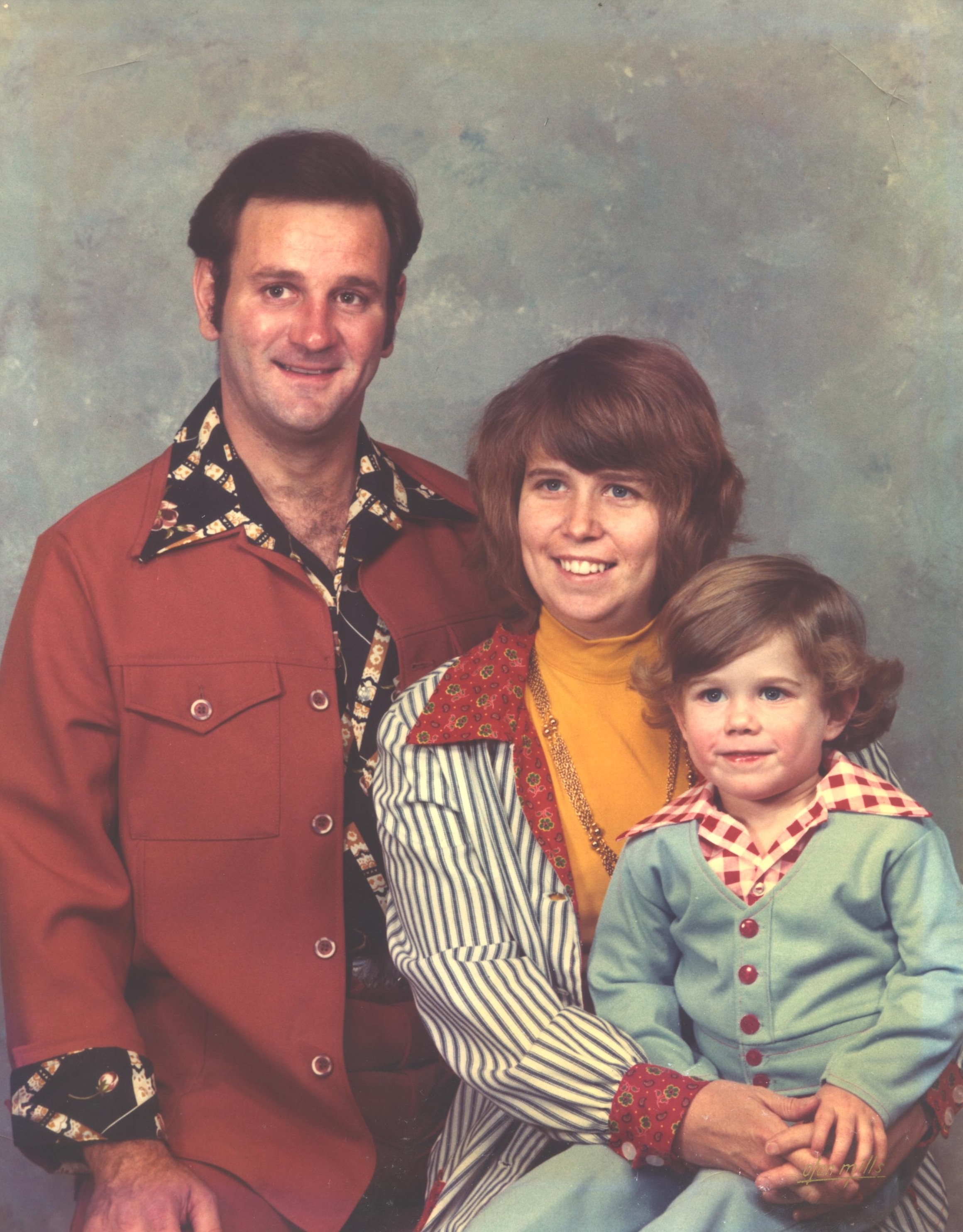

Even my father, Cal, a man whose presence in my childhood was fleeting, confirmed similar concerns when I was just a baby. In a blunt and direct dialogue with me years later, after a heart attack had stripped any need for pretense, he recounted a moment of conflict with my mother, Patricia, when I was just an infant - a time when I should have been the object of unconditional protection. Instead, in a display of what can only be described as tactical cruelty, she had lifted my small body and used me as a literal shield against my father. I do not believe my father was a physically violent man - his rare acts of corporal punishment were invariably followed by a palpable and a gut-wrenching wave of his own regret - worn like a mask of shame upon his face - that he was unable to hide. That image of shame speaks volumes of my memory of him. Obviously, in his rendering of the events, he staunchly claimed there was never a physical threat that warranted a need for protection. From my experiences with the man - the visuals locked inside my head - I believe him.

But, that singular moment clarified a dynamic that would persist for decades: I was not a son to be nurtured by Patricia, but an object to be used and a tool for her emotional regulation. Her rejection was a constant that I would spend the rest of my childhood trying to overcome. I would try to be more helpful, more quiet, more compliant - more of whatever my mother needed to love her child - to love me. I thought I might finally be worthy of her affection if I somehow became that which she had rejected me for not being, having, or possessing.

Most of my pre-school existence was defined by the four walls of my bedroom. I was, for all intents and purposes, in solitary confinement. I was locked away for most of the day in my small bedroom on Eastham Lane - a convenient method for my mother to avoid the burden of my presence while she immersed herself in her soaps or simply existed without me. The memories from that time are a collage of sensory impressions: the suffocating isolation, the disembodied sound of her screaming at me to stay in my room, the pervasive atmospheric sense of being profoundly and fundamentally disliked.

The more dominant of my sensory recollections of that time are of fear and the need to hide. In the Polaroids of my mind, I clearly see myself trying to manufacture places to hide in my small bedroom where I could seek safety. Hiding underneath my sheets was not enough. I clearly recall sitting within my “toy box” trying to close the lid while also positioning all the toys so I was not clearly seen should she open that lid. It was either my “toy box” or my closet. But, within those 4 walls, there really was no safe place. It was still my mother’s home and her room. It was in that solitude, in that crucible of neglect and fear, that I began a lifelong pattern of trying to solve the puzzle of my mother all while also figuring out how to protect myself from her as well.

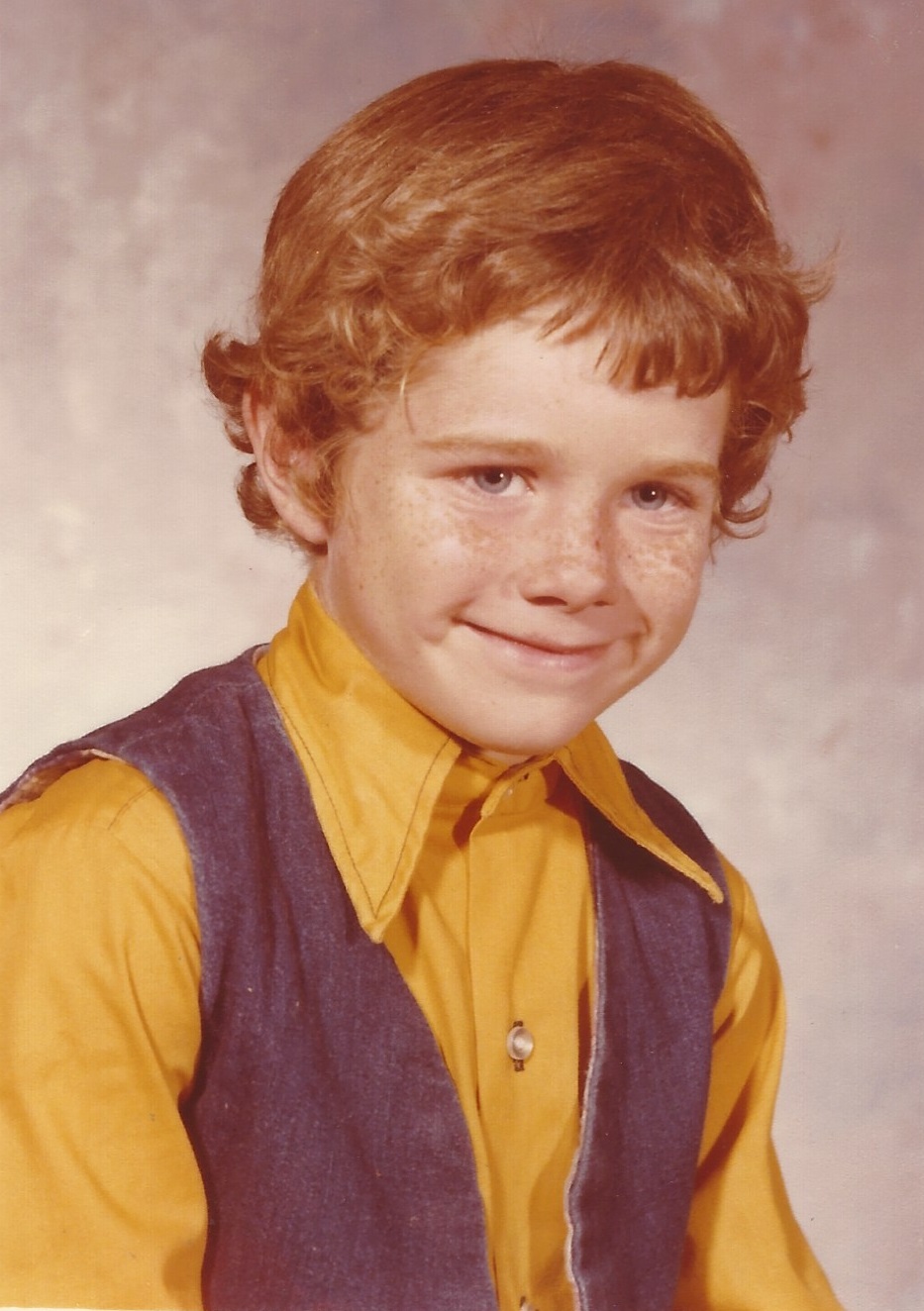

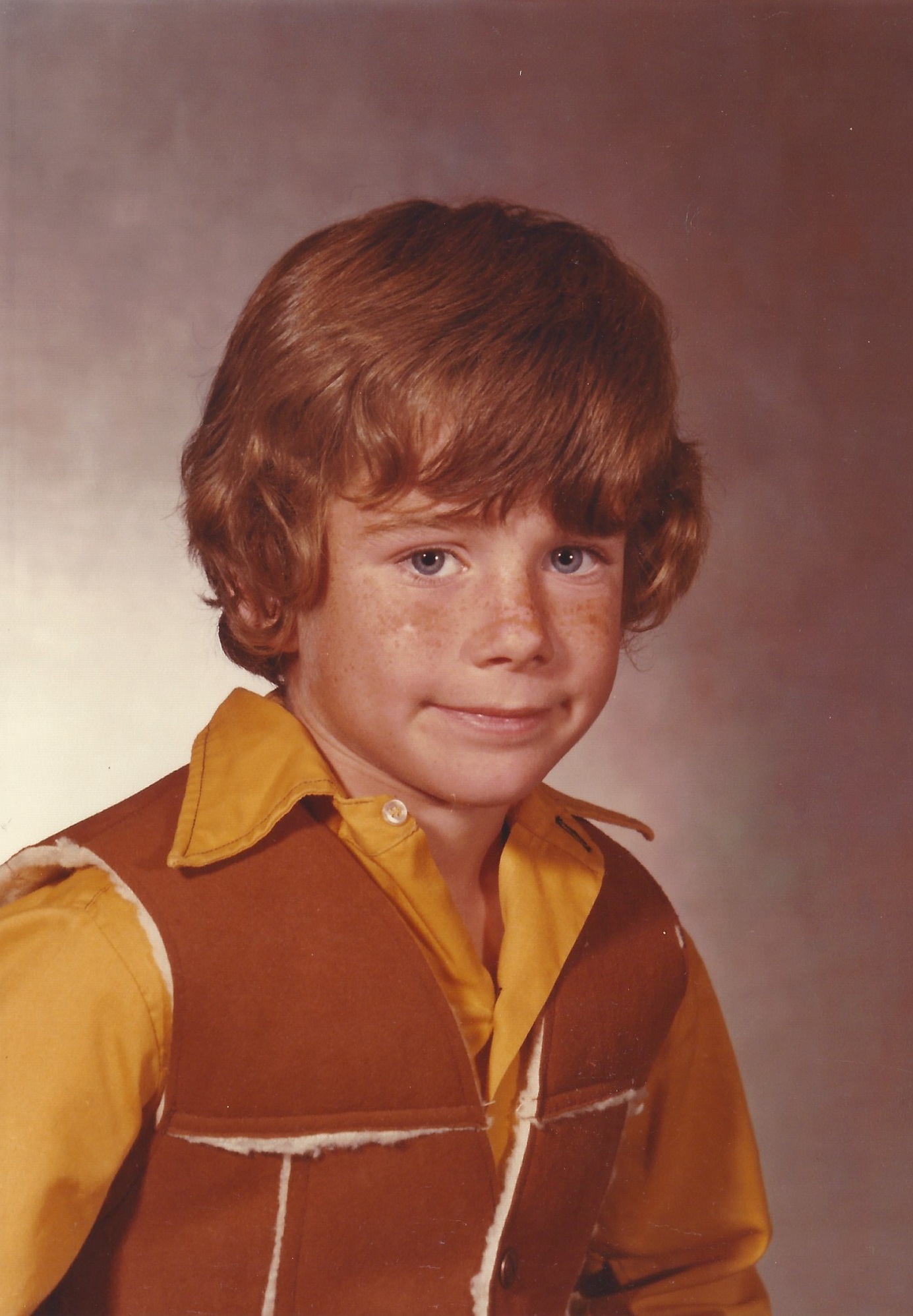

While locked in that room, not only did I hide and battle my fear, but I also struggled to make her like me. One vivid attempt in the photos of my mind was making tape recordings. I knew she harbored an intense fantasy of her sons to become musicians. She frequently discussed among visitors to the house how mine and my brother’s name had been chosen because she hoped we’d be like the “Chad & Jeremy” she had liked so much in her youth. Clinging to this hope, I spent countless hours with a toy tape recorder trying to force my untalented voice into a song that I hoped would please her - satisfy her - make her just like me. It was a secret but a desperate offering I never had the courage to actually give her. Even my aspirations to be a “rock star” later in life and throughout much of my youth was fueled by her desire for me - and in turn my desire to please her.

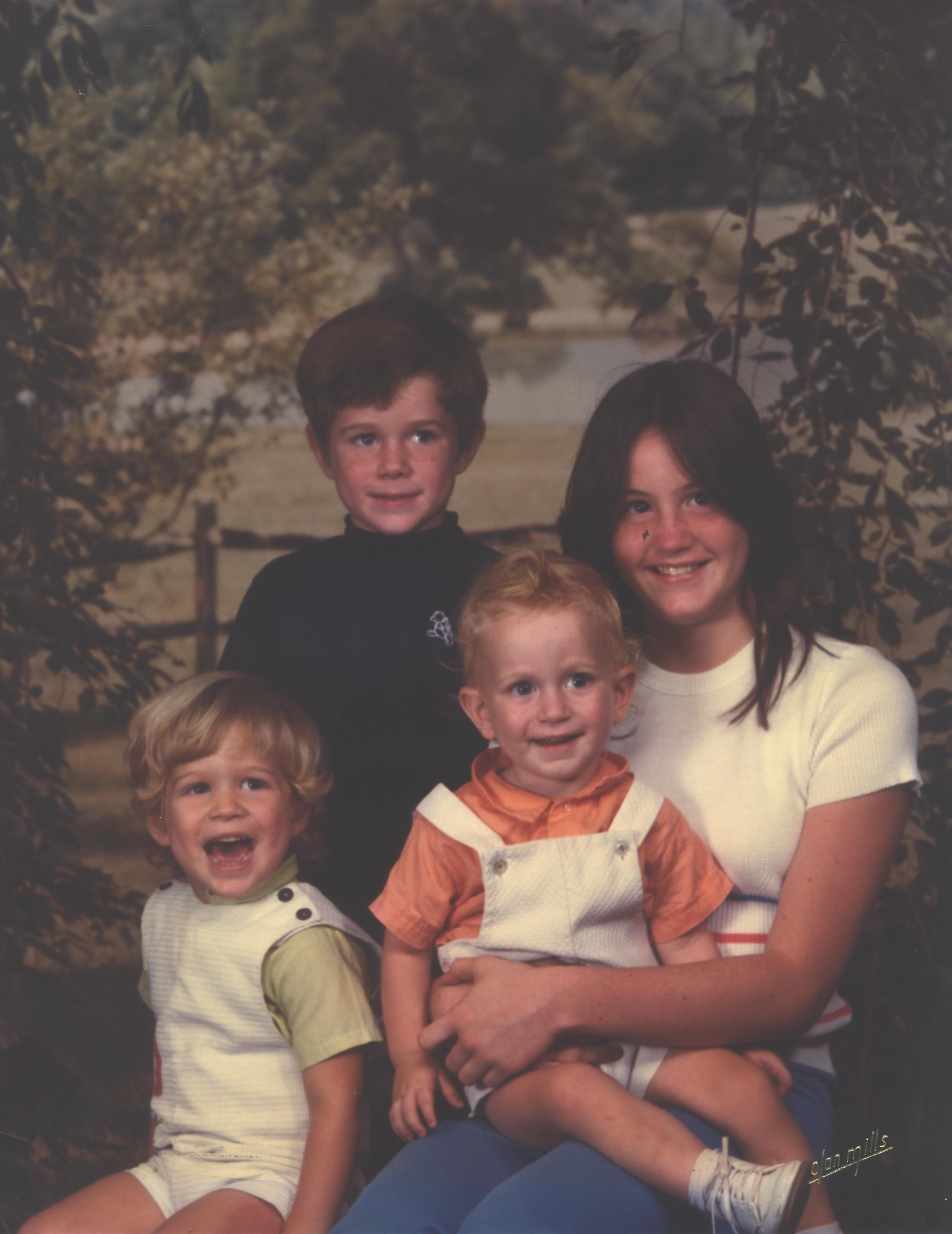

I wish I could say that the cruelty of Patricia Chapman Langford was limited to only the intangible. Sadly it was not. Her violence was not frequent. But, when it occurred, it was fast, intense, and oftentimes, too, too much. Not only did I experience this violence first hand, but then, once my second brother was born so did Jeremy. He too became an inconvenience for her and so she enacted similar, if not more severe, physical violence toward him. In the darkness of my memories, Jeremy took so much more “punishment” than I ever did.

Most of life I have recounted a singular event from when I was a young child to clearly define the wickedness that is my mother. This incident is a visceral symptom of a much deeper, systemic trauma that permeated our household - using the restroom. The fear surrounding defecation was a palpable entity in our home. A specter of shame and potential punishment. We didn’t even use a regular word to refer to it, a word I never uttered in school out of embarrassment because no one else used it.

I don’t recall the specific threats or actions that created such terror for Jeremy and I, but the result is undeniable and has echoed through my entire life. As a kid, I resisted the urge to use the toilet until the last possible moment; crossing my legs, dancing in discomfort, and doing anything to avoid going inside to sit upon that throne. My middle brother, Jeremy, who is developmentally disabled, and thus even more vulnerable, suffered even more acutely; he was still soiling his pants at the age of fourteen or fifteen - when I last saw him - when I left home - a testament to the longevity of this instilled terror.

On one particular day, I desperately needed to go to the restroom. It wasn’t quite diarrhea, but it needed out in a hurry. In a panic, I rushed into the bathroom - terrified I was going to have an accident. The details of how my excrement ended up on the bathroom floor have always been fuzzy. What I do know, in my panicked attempts to get my pants down and to the toilet fast, I had left a small trail of piles from the closed door to the toilet. In my mind's eye, that bathroom is 20 feet long and I can see the piles leading a path to the closed “black” door.

In a rage that eclipsed all reason and humanity, my mother came into the bathroom - finding my mess even before I’d had a chance to try to get everything cleaned up. With a furious rage she took each pile and systematically shoved them one-by-one into my mouth.

I remember my mother holding my head forcibly by the hair as she used her other hand to violently pick up my accidents and shove each mistake into my mouth separately. I can still feel her fingers as they slightly opened so she could push as much in and off her fingers as possible with each violent shove - dragging her fingers across my mouth and face to smear it all in. All the while she was screaming. The only thing I recall for sure that was screamed at me, into me, was “YOU WANT TO SHIT ON THE FLOOR!”

Near as I can recall, this scooping happened 4 or 5 times. In the visual image of the bathroom that has lingered in my brain since age 4 or so, there are clearly 4 distinct piles. But, the sensation of her fingers coming against and removing from my mouth as I screamed, feels like 5 in the echoes of my mental chambers. The real horror of it all is that if I linger on this memory too long, I will start to taste it. If I am somewhere that has a strong excrement smell in the air, I’ll taste it then too. To this day, at age 51, I tend to hold my breath for as long as possible in any shared bathroom environment I enter, potential stink or no. It is a taste, it is a texture, it is a violation, so profound, so absolute, that I avoid anything associated with the most basic of human functions.

The shame my mother instilled in us became a part of my cellular makeup, following me into adulthood and into my relationships with women who could never understand my inability to perform the most basic human functions in their presence, a private humiliation born from a cruelty I could never explain, let alone understand personally until much later in life.

This is the most vivid memory of my mother’s cruelty that I have typically told to define how I am so easily able to live a life with no contact with my creator. The truth though, is that for years, I hid behind the violence of that single memory so I didn't have to delve deeper beyond the surface of not only that singular horrific moment, but everything that my “protector” - my donor - did to me as a child. The truth, there were many more moments of ongoing cruelty that shaped me - well beyond the surface of the just the physical violence. Some have become such ingrained parts of me that I don’t even realize it. Just as I am now realizing as I put these words to paper why I’ve always held my breath in public restrooms.

As I now struggle with severe PTSD at the age of 51, I’m beginning to see how the subtlest of cruelty from a far flung childhood lingers for one’s whole life. My mother was more adept at psychological cruelty. She could cut down an army with the viciousness of her words. Her moments of violence were unplanned explosions, whereas by comparison, her verbal assaults seemed more like masterfully planned methods of assault, prepared well in advance. These did so much more damage than her physical abuse. These lessons sowed a lifetime of self hatred, masked as self doubt. Of all her verbal cruelty though, I think the most lingering was the constant and daily belittling of “you’re a bum” or “you’re a loser” - “just like your dad.”

It’s now that I really struggle with the day to day functioning of life because of PTSD that I hear these words constantly playing in the chambers of my mind. All the while, it’s my mother’s voice continuing to convince me of my lack of worth.

With my brother Jeremy, it was “you’re stupid!” A cruel insult to hurl at a child who was officially diagnosed as developmentally disabled - some even used the now forbidden language of “mentally retarded” to explain away his difficulties. I have too many memories of her hurling that phrase at my middle brother like machine gun fire while she repeatedly slapped him on his head. It was only recently where I found myself doing something similar - to myself - and with my own hands in an extreme PTSD moment, all while screaming at myself in my mother’s voice “you’re stupid,” that I came to consider that the same was probably also done to me before Jeremy came to exist.

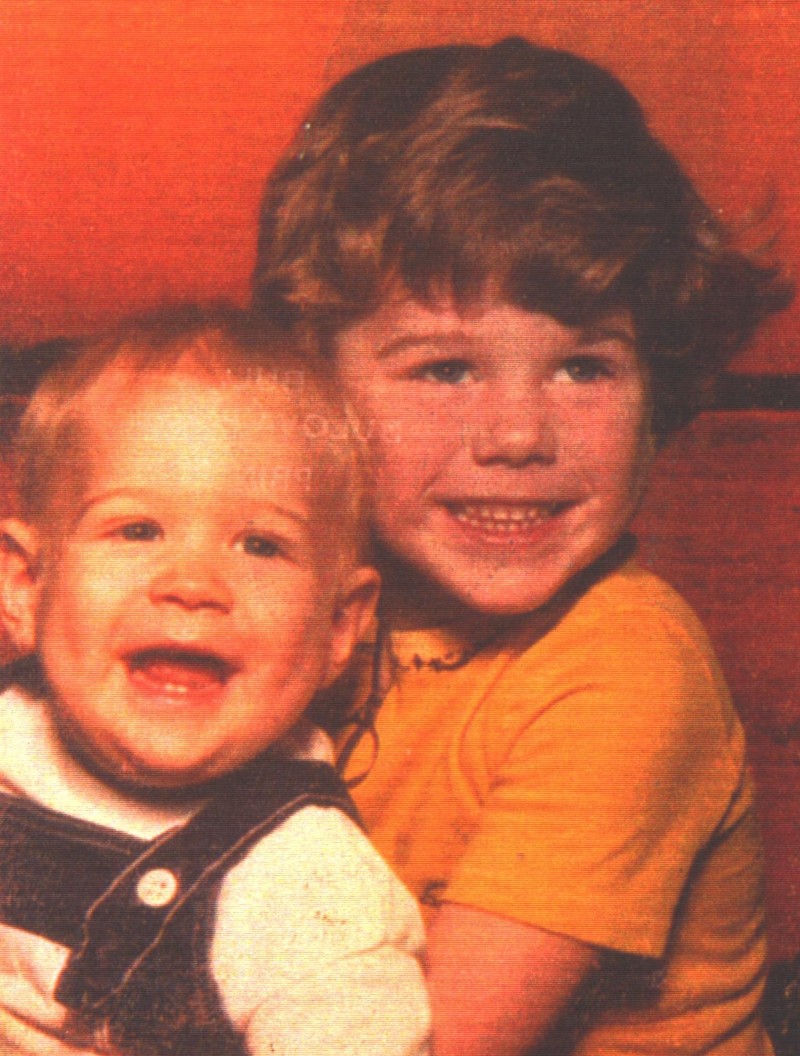

One fact that I do know is that after the birth of my brother Jeremy, much of the physical violence that had been directed at me shifted toward him. The violence toward me lessened as it increased toward Jeremy. In all honesty, that’s just another part of the shame that I have always carried regarding my brother Jeremy. I was about 3 and a half when Jeremy was born and I was so excited to have a baby brother. For the first 14 months of Jeremy’s life, he was my best friend and we were inseparable. I gave him all the love that I had - that I wished my mother had for me. When my younger brother Billy came along, I dropped Jeremy like a child getting a new toy for Christmas. I know I hurt him. I have always been very empathetic and I think my earliest empathy moment was Jeremy’s own hurt from my sudden rejection of him. I think what hurts the most about that memory is that I saw Jeremy hurting but I still chose to throw him aside in favor of the new.

I don’t know how soon after that Jeremy began to show his developmental challenges. I do know that, to me, overnight he started acting differently. A new Jeremy that became that much more exasperated by the abuse meant for me, now being redirected at him, by our mother and further intensified by my own abandonment of him.

Looking back on all of it now, I don’t recall Billy ever being the recipient of my mother’s rage. I know that when I was about 10 and suddenly put in charge of the two of them, I utilized the same violence that had been used on me by her directed at them in my care taking of those I was meant to protect - should have protected. That’s something that sickens me even to this day as I know violence has never been a part of who I am or what I want to bring to the world. I can recall from a similar time at Eastham Lane, neighborhood kids torturing and killing lizards with their bicycle chains. That imagery still lingers in my mind and hurts me just like each death I actually saw when I was a child. I know that the violence of my mother I took up for a period, was never apart of who I am, who I ever wanted to be. But, I have to acknowledge, that I did the same to my brothers when it became my turn to take care of them.

I am striving to be as openly honest as I can with my words here. This has actually been a compulsion my whole life because of my mother and her lies. As an abused child, one doesn’t know that what is happening, is wrong. It’s just the norm - it’s just, all we know. But, when you’re told early on that lying is wrong, it becomes perplexing when witnessing one own parent always lie. I never understood why in those early years. But the collage of feelings from that time include shame. Shame for knowing my mother lied about me and shame for not defending myself. Shame for not proclaiming the truth. Most of the lies were little while lies most likely intended to deflect from the days events and my injuries. But, as a young child I just recall screaming inside “that’s not true!” “Why is she lying about me?”

My mother’s lies weren’t strictly limited to the little white ones about me either. I recall frequently being roped into and required to lie on her behalf. My first memory of this involved a cracked skull and a visit to the ER. As near as I can recall, I was around the age of 3 or 4. My mother, frustrated from my delays in getting off the swing set to come with her, forcibly yanked me off the 1970s metal swing set my father had established in the yard for me. What exactly I actually struck my skull on, I do not know. What I do know is that I was told that I had to say that I hit my head on the concrete around the posts of the swing set - something my mother had been complaining to my father about for a while. I was to tell the lie that I had somehow fallen and struck my head on that concrete. As near as I can tell, I still have a dent in my skull to this day from that fall - because of that lie.

This was just the beginning of the lies and the beginning of my being required to lie on her behalf. When I was in 4th grade, my mother threw a coffee cup through a window in a rage about my father. I was instructed to say that a ball was accidentally kicked through the window from outside.

My mother’s rage wasn’t always in full control. When I was in fourth grade, maybe 5th grade, my mother kicked the back of another woman's car in a King Soopers’ parking lot. She ended up getting sued in small claims court for that kick and the resulting damages to the woman’s car.

On that day, my mother was waiting to pull into a parking spot and this woman swooped in and took it despite the fact that my mother had been sitting there allowing this other woman to pull out. Trish got violently angry and I recall her screaming and yelling in the car. I don't think she screamed and yelled outside of the car. But I have a very clear memory of her calmly turning and lifting her leg as high as she possibly could so that she could kick above the bumper as she slammed her foot into the back of this woman's van. I must have been further behind her getting a shopping cart because the visual in my mind's eye has enough distance between my mother and I that I could see her full body as she kicked this woman's minivan.

In this instance, I don’t believe my mother asked me to lie for her though. I think that seeing her lie so frequently had made it seem ok to do so - to protect her - a strange internal need that I still carry to this day. A need that even makes writing the truth challenging for these hands that have seen more time away from her than ever had with her. I know that she vented to me frequently. So, I heard quite a bit of her complaints about the incident with the van. The majority of them were that she did not dent that woman's car. My mother was very adamant that she had kicked the car with the flat of her foot and therefore she could not have possibly left a dent - “no way, no how.” On the day of the trial I was asked to take the stand to testify. I said something to the effect of seeing a dent below where my mother had kicked after she had kicked the van. I think I was trying to say that there was a dent there already and I happened to notice it after my mother kicked the van. I don't think I was specifically instructed to lie in that fashion or with that specific detail. Rather, and this would match up with my adult inklings, I think I was trying to protect her. And in my 10 or 11 year old mind, that was the best way that I could come up with to defend her.

The strange thing is I won’t do that as an adult. As an adult I am very offended by dishonesty and have even cut off friendships because I didn’t agree with how one had been dishonest. But I do go out of my way to help those in need. I have very clear memories of trying to help others all the way into my childhood. That behavior of the younger Charles on the courtroom stand was his juvenile attempts to somehow protect his mother while employing the same tactics he’d seen her frequently use over the years. I committed perjury at the age of 10 or 11 to protect my mother.

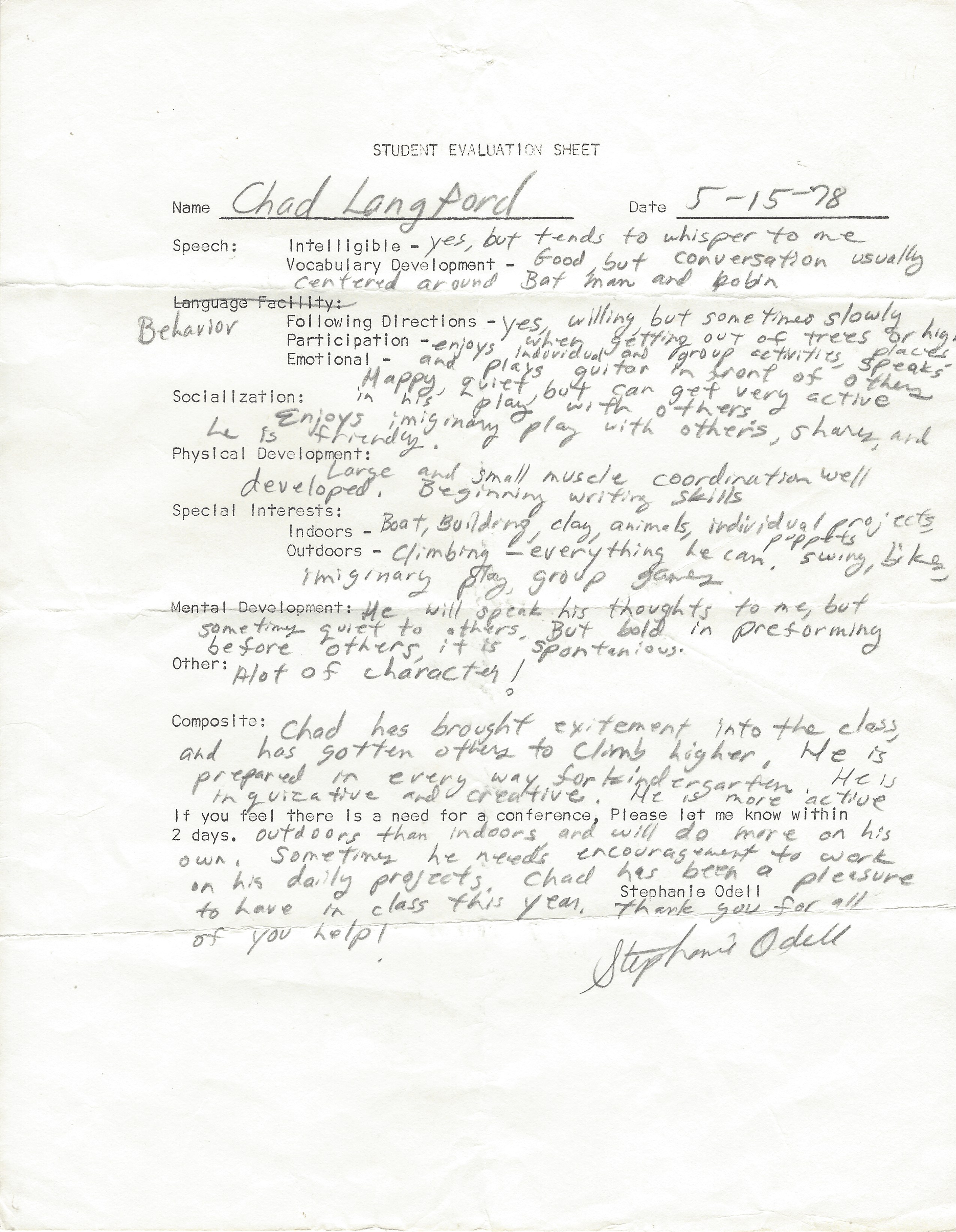

As noted above, a child doesn't know they are being abused. It’s just the normal that they have to function within. In my case, it was survival. But, it’s well known that abuse at home contributes to distrust of others outside of the home. My first attempt to seek help from the world beyond my home, an act of autonomy, occurred when I was about four and a half, during the summer of 1978. Granted, I wasn’t seeking help for the abuse but rather arrangements had been made for me to attend a speech class. I had an impediment where my 's' sounds came out as and “f” sound. For example, “Spider-man” was pronounced “Fighter-man.” I escorted myself to the school that summer day - tasked with navigating an adult world. I remember standing in the office, trying to announce myself and to explain my presence. But the words came out wrong. I remember the confusion on the faces of the office staff, and then the moment of dawning amusement. A man laughed at my "feech" and made a joke about the beach, “you’re far from the beach!” The office staff, taking their cue from him, joined in on the laughter.

In that moment, all I felt was shame. At home, expressions of emotions were not welcome. In my attempts to express myself, I feared I showed frustration - another unwelcome emotion with my mother. I was ridiculed and my vulnerability turned into a source of entertainment for bored adults. I was dismissed, a lesson in the futility of seeking help learned far too young - a lesson that would be reinforced time and time again - influencing any and all future interactions with people in general. Taunted at home and laughed at in public, I gradually learned to turn further and further inward.

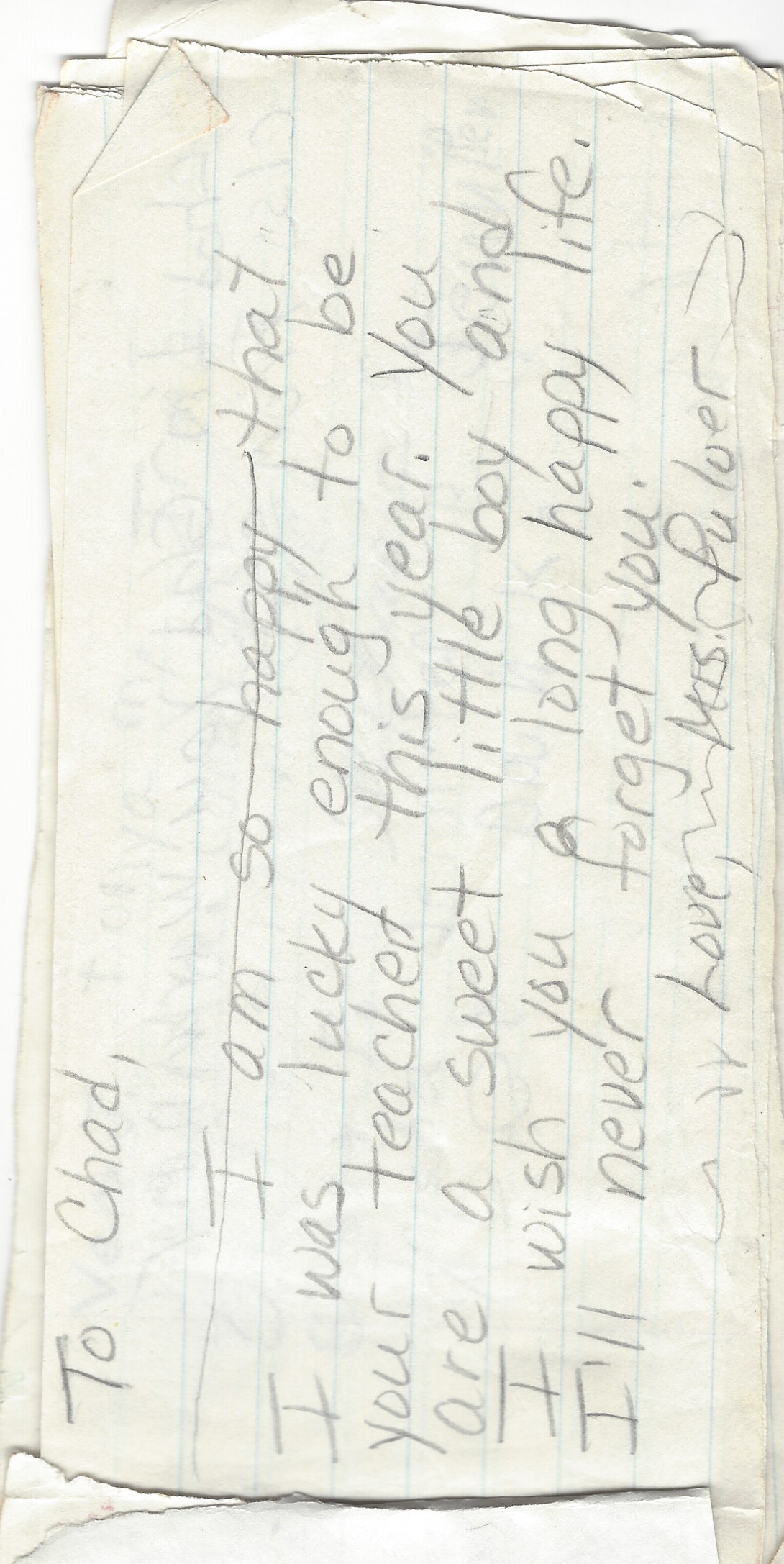

The ultimate betrayal came my first time going through kindergarten at Butterfield Elementary School. A moment of comfort turned to magnified shame. The teacher, Ms. Reiss, had picked me up and put me in her lap. She held me as I sobbed - for what I still do not know. But, I felt no comfort in her arms and from her gentle hugs and squeezes. I specifically recall being in her lap in front of all the other kids, sobbing uncontrollably and simply feeling betrayed. I could see all the other children through my tears and her caressing of my face. My memory is long, but all I can see is that all the eyes of the other children were on me and I did my best to avoid them - trying to keep my eyes on the darker part of the classroom that was not in use. Even though, I’d experienced some mild bullying that first go around in kindergarten, I don’t believe any of the children laughed or that it was because of any bullying per se. All I know with absolute clarity though, is that I was embarrassed, ashamed, and most importantly, betrayed.

At home, my mother never comforted me when I was upset - ever. My emotional pain was something I needed to keep hidden and not show or else my punishments simply got worse. This moment with Ms. Reiss and the other children further instilled in me a lack of trust in others. To show feelings of hurt, could result in more attention. I even began to temper happiness. I already knew that attention was bad from my home life. So, as a sensitive 5 year old in 1978, I further learned that trust in others was misplaced - it drew attention. Attention was not a good thing. It was never a good thing - ever.